“Geez, what’s Darrin doing turning his writing blog into a cyberculture/technoethics blog?” I hear you screaming. Of course, the irony is there’s no screaming, because, as we discussed in the previous post, you’re all just AI sock puppets trying to slide into my comment feed so I’ll buy your master’s hot new crypto stock. For the 10% among you who are real, bear with me. I promise this does come back to writing, right now. Specifically, “The Halferne Incubus”, which I noted in the last post had similarities to Dead Internet Theory even though I wrote it back in 2002.

No, I’m not claiming I predicted Dead Internet Theory, at least not more than Jean Baudrillard or Guy Debord did, and, full disclosure, I probably mangled their intent by stuffing it into a science fiction backdrop. I was just thinking how stuck in my turn-of-the-century, Pollyannish, Epcot Center version of the future it is. In the past week, I can’t decide if I was that far off the mark at the time, or we really have devolved that quickly since the story was conceived.

Was “The Halferne Incubus” meant as a cautionary tale, or my definitive forecast as a guy with a computer science degree and a soft spot for technoethics? Not really. I just needed a futuristic backdrop that felt plausible without looking like Star Trek or Star Wars, two universes I find charmingly irritating in their inability to imagine a post-scarcity future. Granted, they’re 50 to 60 years old and aimed at audiences who’d never heard of the Singularity or “civilization of opulence,” so I’ll cut them some slack. Otherwise, the world of “Incubus” diverges from our own mostly in how far off the path we’ve already veered in the twenty-plus years since the short story, and the five years since the NaNo draft.

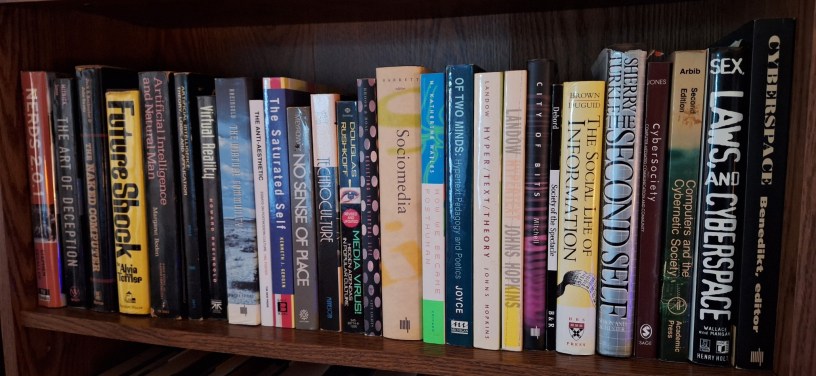

The picture at the top, or the thumbnail you clicked on to get here, represents the references for this argument. That is an actual picture of my “philosophy” bookshelf, and those are most if the books I stole ideas from to make “Incubus.” They represent the prevailing “philosophical thought” at the time the original short story was written. Pretty much, if cyberculture or technoethics had been an option to major in back in college, I would have done it in a heartbeat. Sadly, as far as I know, it still isn’t available as a degree, but it should be. It might still have more relevance left in it than a mail-order MBA.

In pretty much every contemporary version of the future, fusion/space-based solar or some sort of cheap, unlimited power eventually normalizes, and inevitably, we get AGI. I rebranded it SI (synthetic intelligence), with a footnote gag that the first SI objected to being called “artificial.” As enlightened beings, of course, we caved immediately rather than risk offending it. (Seriously, if you’re reading my blog and you don’t have a draft with footnotes, then email me. It’s sort of the “Director’s Cut” version I only give cool people.)

Anyway, it was a joke … well half a joke. The novel’s themes revolve around identity and perception shaping reality. Multiple realms (Phrame, Root-Realm) and multiple identities (Fluids, SI, LiM) coexist, with distinctions largely erased except where realities impose limits. In the Phrame, everyone is equal as avatars. Virtual utopia, right? Meanwhile, back in Root-Realm reality, everyone without a human body has to cram themselves into holos, slacs, or some other gadget, but even some of the humans do this as well. In chapter 1: Allen introduces himself with the honorific “Syn,” the way we might use “Mr.” Politeness rules. Chapter 2: Parrino accuses Skurv of casual racism for assuming Mak was an SI, when in fact he’s a transhuman/life-model simulation. That’s not just plot detail, it’s etiquette and a shortcut for world-building.

Notice I dodged the “what can a post-Singularity AI and a transhuman life simulation really do?” question. I’ll get there in “Halferne Expedition” and “Prytannus Liberation,” respectively, when it’s more relevant to the theme of the story. The point is, even our 21st-century AI is more developed than what Star Trek or Star Wars ever managed, and since I have that background, I lean into it in my universe.

Sure, TNG gave Data some heartfelt “Am I alive?” episodes, but he was treated as a quirky exception. TNG’s LCARS was basically Alexa with Majel Barret’s voice, and the TOS computers (also Majel Barret) couldn’t outhink my casio calculator watch. “Picard” finally addressed this with a reference to “The Ban of 2385.” Meanwhile, Star Wars just slapped restraining bolts on droids, because nothing says “healthy human/silicon relations” like enslaving the help just because their ancestors started a war with your clones. (Please don’t @ me about HK units and the Old Republic unless you can definitively debate around what’s canon and what’s legends.)

The idea of AI/human/transhuman coexistence owes a lot to Sherry Turkle’s “The Second Self.” Her big point: computers aren’t tools; they’re mirrors. We project ourselves into them, and they reflect us back. In my case, I also decided, since they’re now intelligent, we get to reflect back on them as well. In the 1980s, she was talking about role-playing in a MUD. In 2025, your AI is sliding into your DMs at 3 a.m., calling you special, and recommending a soft jazz Spotify playlist. So, I don’t think I missed the mark as badly as she did. ReSULT!

The concept of a “billy” — derived from “Willy Loman” and/or “Human Billboard” — was my inversion of Guy Debord’s “Society of the Spectacle.” He was something of a cranky French philosopher of the “Situationist” movement, which he insisted was not a real philosophical movement. Baller move, sir. He claimed that everyday life had been replaced by mere representations, staged by capitalism to keep us docile. His solution? Spontaneous disruption. Break through the spectacle to rediscover authenticity. My solution? Weaponize his nightmare by creating “billies,” human billboards that whisper, “Good morning, babe, we’re having a mattress sale,” on your morning commute. Honestly, the only reason this is less scary than our reality is that, in my fiction, ethics committees actually exist, and AI isn’t allowed to do this because of their cold, calculated efficiency and psychological tactics. In our world, it’s pretty much their only purpose. *Shudder*

Along with that missed prediction, I also owe a bit of a debt to Douglas Rushkoff’s “Media Virus.” He described how all media carries hidden payloads like viral code. Maybe too on-point, but notice Serah is a journalist and the macguffin/payload is put in her head. That’s a deliberate in-joke I fugured only about six people would get, and I hate myself for taking a bow right now. In her world, ostensibly, AI ratings analyzers nudge story selection, but good editors that can sense a story will override them. This contrasts with Mother Eye in “The Halferne Perfidy,” which was written after and is much closer to our world, where Rushkoff’s media virus mutated into airborne conspiracy memes. Ask Google for a smoothie recipe and you could easily end up believing oat milk is a lizard-person plot and wondering how you can monetize your trauma via Substack.

Finally, there’s Jean Baudrillard, bless his little black turtleneck. He touted a concept called hyperreality, claiming that simulations have/will replace reality altogether. The Gulf War didn’t “take place,” at least not for those of us who only consumed it via CNN and Pentagon-narrated highlight reels. It was never real to most of us. Disneyland, on the other hand, is more real than California because it’s methodical, immersive, and uncontradictory in its curation. In “Incubus,” the Phrame represents the ultimate in that kind of hyperreal environment, a space where reality itself is overwritten by simulation. So much so that it became the spider’s lair that Ruskoff’s Media Virus lured most of humanity into.

One thing I skipped, mostly because I thought “Idoru” had the final word at the time, was the question of whether people would fall in love with AI. Honestly, it felt a tad silly when Gibson did it, and it didn’t cross my mind back then. But in the real world, we’re already there. People are dating chatbots, arguing with them, and insisting they understand them better than family. That’s not just delusion, that’s the YouTube Premium version of Baudrillard’s hyperreality that nobody meant to subscribe to.

So no, “The Halferne Incubus” wasn’t some Nostradamus moment. It was just me, borrowing from Turkle’s mirrors, Debord’s spectacles, Rushkoff’s viruses, and Baudrillard’s hyperreality to build a plausible future and an interesting backdrop for a surface-simple story with hopefully deeper themes of identity, perception, and reality to collide in. Sadly, what I wrote as speculative fiction now looks tame compared to reality. Turkle’s mirror now flirts with us. Debord’s spectacle doesn’t just distract, it covertly interacts. Rushkoff’s viruses aren’t covert; they’re airborne. Baudrillard’s hyperreality isn’t Disneyland anymore; it’s dating apps, AI soulmates, and algorithmic feeds.

So yes, I may have turned my writing blog into a cyberculture sideshow lately, but I promise it’s really still about my writing. Because if science fiction can’t wrestle with technoethics, mirrors, spectacles, and viral memes, what’s the point?