Once upon a time, before .NET turned programming into Ikea furniture assembly, I had a little thing called grimoire.dll. It wasn’t a framework, or a dependency, or whatever fashionable euphemism we use now for “someone else’s code I don’t understand.” It was mine. Welcome to another segment of classic tech rants and reminiscences that I should probably just call “Adventures of a Grumpy Old Coder.”

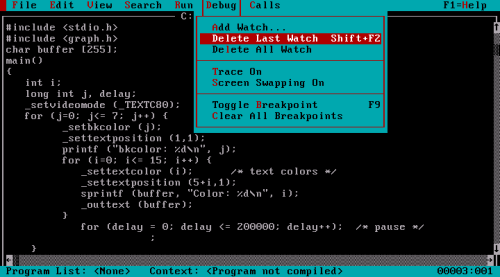

Anyway, inside grimoire.dll were the crown jewels of mid-’90s enterprise hacking: a calendaring system that actually worked across time zones; a popup-menu library that could let you call your program’s subroutines out of context, map your mallocs and _fmallocs, peek in on memory blocks, watch individual sectors on your hard drive, general debugging stuff in the days before we had visual interdev; a “print to screen” routine that was three times faster than what came packaged with standard C, that I “borrowed” from Max Fundenberger and added markup language around; and, hidden deep inside, a secret keystroke that launched a game of Space Invaders using the contents of whatever text was on the screen — a document, a sales forecast, etc. — as the enemy fleet.

That was my masterpiece. It was 175,000 lines of handcrafted logic that followed me through a couple of jobs, holding entire companies together. I didn’t “import” anything. I didn’t “npm install” a personality. I typed it all in a glorified text editor in monochrome because Visual Studio and even IntelliSense were still 4 years away. When something broke, I didn’t file a ticket; I swore loudly, fixed it, and went back to coding like a person with purpose and a caffeine deficiency.

These days, .NET and Visual Studio give you all that stuff for free. Provided you don’t mind yours looking like everyone else’s. Calendars, menus, printing, logging, error handling, authentication—served up by whatever JavaScript flavor of the month promises to “reduce boilerplate.” Except, of course, for the Space Invaders. Nobody’s thought to include that yet, probably because it doesn’t monetize well.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not anti-progress. I love that we can spin up a Kubernetes cluster in less time than it took my modem to dial Compu$erve. But something’s been lost along the way. Once upon a time, programmers had to understand every line of what we built. Today, half the job is deciphering which package just broke because one of the six guys with his hands in it just rage-quit on Twitter.

I got a computer science degree back when we had to manually code B-trees, heaps, stacks, hash buckets, and file locks. We didn’t just use data structures; we understood them. We could rebuild or redesign them from scratch if we had to, and often did. Now I talk to senior developers who don’t even know what those things are. I meticulously wrote the mechanisms they now drag-and-drop from some magical toolbox, or “declare intent” to implement with YAML, like casting some weird spell. I earned my recursion scars the hard way. They just summon functions.

Back then, we didn’t need frameworks. We were the framework. We couldn’t grab something off Stack Overflow because it didn’t exist. When we wanted to print bold text on a green screen, we wrote our own ANSI escape codes and liked it. You knew a programmer by the calluses on their fingertips and the look of haunted pride that comes from following pointers and tracing memory overruns at 2 a.m.

I mention this because I just finished my first Terraform deployment last week, and this week I’m flying solo with it for the first time. Well, not really “solo,” we have branches, pipelines, and approvers now. Back in my day it was “he who held the one true floppy.” Did I mention networked PC’s were a rare and expensive thing back then as well? There were floppies, and this thing called a “LapLink Cable” … but, I digress.

The point is, I’m glad to be back to writing code for the first time in almost 20 years, but deploying via Terraform feels like building a Lego car, only there are a couple of spots you can deviate from the instructions on the box and make it yours. I’m sure my team thinks of me as the cranky old man muttering about recursion in the corner. They look at me funny when I mention TSRs, or explain that “memory management and cleanup” used to be something you did manually, like mowing your lawn. Their world is APIs and SDKs; mine was hex editors and sheer spite.

For all my complaining, I never did let it go. Every time a junior dev spins up a shiny new React front end, part of me wants to reach over and say, “That’s cute, but do you even know where your print routine lives?” They don’t. They just assume it’s out there somewhere in the cloud, humming along faithfully, like a benevolent god of boilerplate. They’re just happy their code runs. I do miss that. Grimoire.dll wasn’t pretty, but it was mine. When I compiled it, you heard the hard drive on that old XT spin for 15 minutes until it made that satisfying thunk and you got your Compile complete. 0 errors. 27 warnings. message and your cursor started blinking again. It didn’t need a license, a token, or an update every six hours. It just worked.

That’s really what I miss most: the feeling that code wasn’t disposable. It was art. It was personal. It was the product of one slightly obsessive mind who thought, “You know what this ERP needs? Space Invaders.”

Now, everything’s frictionless, modular, and “maintainable.” You can build a company without ever knowing how the calendar works, or what happens behind the scenes when you hit “print.” But you’ll never feel that particular thrill of sneaking a game into your own software and watching the CFO accidentally vaporize his own revenue forecast.

Let’s also point out that this is exactly why one bored teenager with a YouTube tutorial can write a single virus that compromises 80% of the world’s companies. Everything’s the same now—standardized, abstracted, interconnected, and conveniently hackable with the same exploits. Back in my day, nobody hacked me. Script kiddies didn’t even try because it would’ve taken effort.

Maybe that’s why I’ve taken to writing novels for fun, when I used to write software in my spare time (okay, sometimes I still do, just less and less frequently). After decades of watching my code get swallowed by frameworks, my recursive subroutines replaced by “intention,” and my craft sliced into agile stories, fiction feels like a final refuge of control. When I write a novel, it’s mine again. There are no third-party libraries, no approval pipelines, no one “declaring intent” to co-author my sentences. Just me, the keyboard, and the story. Every plot twist, every typo, every bit of accidental brilliance belongs to me.

Except this time, the easter eggs are more cleverly hidden.

Did you use Borland C or Pascal when you coded that?

I hear what you’re saying. Back when I started coding, one of my first projects was to fire a triac at whatever degree along a sine wave in real-time, in order to extend the life cycle of a relay switch, any relay switch, could even be the one under the dashboard of your car, the in parked I your driveway right now.

That was back when the desktop computer was an 8088 4.77 MHz processor.

I took pride in writing assembler operation codes by hand and adding enough NOPs in the loop to get the timing right. I’d poke those codes into the RAM on a single board computers. No compiler needed.

Programming real-time on real hardware by hand. It doesn’t get any better than that.

LikeLike

I started on Borland Turbo Pascal, but my first professional job was Microsoft Quick C 1.5. I wrote educational software that triggered a custom piece of hardware to listen for DTMF tones on a telephone line to played raw audio files along with what was on the screen. So, lots of interrupts, bits of inline assembler code to buffer raw binary audio streams to a jerry-rigged PC speaker and watch a DTMF receiver for new tones. It was glorious.

LikeLiked by 1 person